Someone once explained company operations to me like building a music studio. You have to build the walls, install the soundboard and the audio panels, and place the equipment so the musicians can come in and jam. Companies are like that too. You have to build the unseen systems that underpin the day to day so that the PMs, Engineers, Designers, and Data Scientists can build great things, aka jam.

The most foundational system is our operating model - the cadence at which we establish our strategy, execute on it, and evaluate its results. Our strategy is like a living organism. It’s never “done”. Our operating model keeps it alive. It is arguably the most important product we’ll build and maintain, and we must approach it as such.

Our operating model is made up of the planning-execution-review cycles for different parts of the company. The highest level of abstraction of our model is the annual cycle. Prior to the start of each year, leadership determines the goals for each component of our company equation and the inputs we’ll work on to reach them. These goals and inputs make up our company strategy. They are designed to encompass the year ahead and will be in the format ascribed by our strategy framework (OKRs, Playing to Win, etc.). How we will work on these goals and inputs might change throughout the year but the goals and inputs are fixed. This is the only part of our strategy that is top-down. How we will work on our inputs will be determined by the teams working on each of the inputs, bottom-up.

Next, the Finance team uses this company strategy to create an annual financial plan. This financial plan includes an annual budget outlining investments we’ll make throughout the year and a forecast of the returns of those investments. We’ll operate against this financial plan throughout the year, iterating on it as necessary.

The cadence of the next level of abstraction depends on the company’s stage. It could be bi-annual, quarterly, or monthly. Newer companies with less product-market fit have shorter cycles until they get their product-market footing - planning, executing, and evaluating experiments swiftly. More mature companies will have longer cycles.

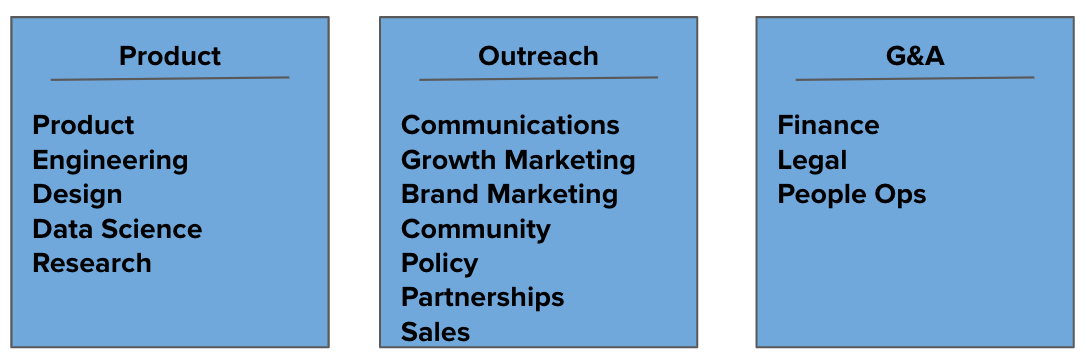

Before we start planning, we must break up the company into pillars that will be planned for, executed on, and reviewed. Companies can be divided into three parts:

Product includes the organizations that deliver the products. Outreach includes the organizations that amplify the products out in the world. G&A includes the organizations responsible for supporting Product and Outreach work with resources.

Each of these pillars has its own planning, execution, and review cadence, but they all have dependencies on each other and their work needs to be planned for, executed on, and reviewed at a cadence that complements and drives the others.

Once we have our financial plan, Product planning begins. Product determines how we’ll work on the inputs outlined by leadership to reach our goals. The deliverable for Product planning is a Product strategy for each team working on an input in the format ascribed by our strategy framework, and corresponding roadmap.

Once we have our Product strategy, Outreach planning begins. Outreach planning operates on the same cadence as product, just trailing it. Outreach teams use the Product strategy to create their Outreach strategy outlining the work they will do to amplify the products that Product delivers.

After we finish our Outreach strategy, G&A planning begins. G&A planning operates on the same cadence as Product and Outreach, just trailing Outreach. G&A teams use the Financial plan, Product strategy, and Outreach strategy to create a G&A strategy, outlining the work they will do to support work across the pillars. This includes a headcount allocation exercise to ensure teams have the headcount they need to deliver promised results. Then the strategies make their way back to Finance who ensures that the all our plans track to our financial plan.

I know what you’re thinking. This series of planning cycles sounds time consuming and it can be for leadership. The trick is to time it in a way and design the planning sessions so that they don’t detract from our execution cycles, while remaining bottom-up.

Once we finish planning, we start executing. Our execution cycles are bookended by our planning cycle and our review cycle. They last anywhere from four to twelve weeks, depending on our model’s cadence (and the maturity of the company). During the execution cycles, we give our strategy time to demonstrate results while continuing to check-in to see how the work is progressing via regular meetings with our teams and close attention to how metrics are moving day-over-day and month-over-month. Once in awhile we’ll realize the strategy is off mid-cycle and we’ll want to change things but if we’ve done adequate critical thinking during planning and we’ve timed our cycles appropriately, this should happen infrequently.

At the end of our execution cycle, we evaluate our results - did we hit our goals through the work we did on our inputs? If we didn’t hit our goals but we did complete the work we set out to do, this means we chose the wrong strategy. It’s possible that we hit our goals but they weren’t driven by the work we did. This would mean we’re doing the right things but we don’t know what they are. Once we complete our strategy review, we go back to planning, using what we learned from the last cycle to begin the next.

These cycles for the three pillars come together in an annual Operating Calendar. Our Operating Calendar outlines each of the planning, execution, and review cycles for the year. It’s owned by the Operating Model Administrator who will use it to plan the meetings and deliverables for every phase and checkpoint. Oh, yes! Our Operating Model needs an administrator who is the “brains” of the operation. More on this in the next post, but this person must know the company like the back of their hand and drive every part of the model day-over-day, week-over-week, month-over-month, and quarter-over-quarter.

These planning, execution, and review cycles sound like a lot of process but they don’t have to feel like process. Actually, they shouldn’t feel like process at all. Every phase, meeting, and document outlined in the operating model is a touchpoint, a moment when we bring together the right people, equip them with adequate data, ensure they have adequate mind-share, and put them in the right conditions so they can effectively come up with new ideas and solve problems with existing ones. It’s the walls of our studio, so our people can jam.